I traipsed jauntily down the drive way and past the oblong rose garden in red bell bottoms and a tight parrot green and brown checked shirt— a loquacious, pony tailed five year old with two missing front teeth— past the guava and custard apple orchard, the low orange and sweet lime bushes, out of the tall iron gates, along the long winding road and towards the Birmitrapur Officers’ Club. Vikram mama, whose finger I clutched, always pointed out the fireflies in the dark foliage, and then I’d walk with my head thrown backwards facing the myriad stars in the inky black December sky; a breathtaking sight seen only in such far flung places in India’s interiors. Even before we reached the top of the hill and caught a glimpse of the imposing faux colonial structure, we usually caught the strains of Cliff Richards’, “Theme for a Dream” or a Peter, Paul and Mary number or even some 1970s vintage Jagjit and Chitra Singh wafting with the breeze.

Every Thursday and Sunday, of those glorious six months of 1976 and every subsequent annual trip to Orissa that I went to my grandfather’s place in Birmitrapur, Orissa, all of us from the Patnaik clan and the other families— from the houses dotting the hills— would descend in a sizeable number for those magical film screenings at the club. Birmitrapur, in northern Orissa, has one of Asia’s biggest limestone mines, an offshoot of the Bird Company (where Amitabh Bachchan began his career as an accountant); it is a small hill station, and the club and the officer’s bungalows are nestled in the hills and their crests and troughs.

There were actually two clubs in Birmitrapur adhering to a certain hierarchy of officers and staff and workers. The Officers club was for officers of a certain standing and rank, a more elitist affair; while the other, the more popular Bisra Club, was for all staff members. Films were screened there as well, but only once a week. As for the workers in the mines and other junior staff, films were screened at a vast maidan twice a month. Many people with film watching experiences at such clubs in other parts of the country have similar tales to tell of class distinctions that existed. More often than not, the hoi polloi had to rest content with sitting behind the screen and watching the movie the reverse way, akin to the now-made-famous sequence from the recent Swades.

I am told now that in the 1950s and 1960s, films were screened only at the antediluvian but grand Director’s Bungalow, twice a month. These were English films mainly catering to the tastes of the top officers and the sizeable Anglo Indian community at Birmitrapur. The Director himself lived in Calcutta and showed up in Birmitrapur only once in a while. The film reels were always brought to Birmitrapur from Calcutta, sometimes routed through Rourkela to be screened at the local Community centre. Later, in the seventies, on popular demand, the Officers’ Club started screening home-grown Hindi movies as well. The movies were usually ones that had been released a couple of years ago, but considered recent enough by the community to generate a great deal of excitement.

Even as I shake those sepia tinted memories out of my head, I hear the clinking of ice in slender Belgium glasses, and the soft murmur of conversation, smell the smoke of Davidolf cigars and the succulent seekh kebabs from all those years back. I see Akhtar, tall and imposing, behind the counter serving drinks to all—Fanta and Coca Cola were the fashionable succour of the young and the terribly young those days before they were unceremoniously banned sometime in the ‘70s.

Soon, everyone except the uninterested would drift toward the room where films were screened on a white portable screen. The latter would sit at the bridge tables with their cognacs or coffees; occasionally, deliberating upon national politics, always munching thoughtfully over the ambrosial fare that Akhtar churned out periodically from the inner recesses of the kitchen. Some intrepid from the ‘60s generation who crinkled their aquiline noses at the ‘banal’ and ‘silly’ Hindi cinema preferred to assemble in the lounge playing chess, or table tennis or listening to the then current rage, Come September.

The room, where films were screened, was a large room with wooden chairs— not the kinds to recline on. Children sprawled, usually, on a rug in front. Sundays were for English films and Thursdays for Hindi ones. There was always a full house on Sundays when people assembled, all agog, at around 7.30 pm. Those were times before Doordarshan made film watching at home, at first, a unique novelty and then a matter of weekly routine; long before cable television reduced it to a rubble of pedestrian mendacity.

Even as the reel was loaded on the huge 1950’s Bell and Howell 16 mm film projector, that the club owned, the Mrs. Shastrys, Mrs. Rastogis, Mrs. Agrawals and Mrs. Roys would swap guava jam recipes, extrapolate on how adding a little salt to the oil on the pan prevented dosas from sticking to the pan, how Mrs. Raju had added two more rare partridges and one more Cheetal deer to her burgeoning wildlife family, how Mr. Patnaik had again bagged the first prize for gardening for his grafting of many differently coloured roses on the same shrub, and how so and so’s second son was not doing well at the REC, Rourkela. Mrs. Whiggs and Mrs. Rodericks would discuss, in low tones, the possibility of moving to London in a few years, or sending the Loilas and Lindas or Melvins away for higher education. The children munched away at sandwiches, chattering endlessly about the new Games Master at school or about Rai’s or Runa’s upcoming birthday party. It was a small world; everyone knew the goings on in everybody’s house.

When the lights were turned off and magic unwound on the silver screen, there was always a sudden hush and very palpable excitement. It was nothing short of sorcery at work and everyone was simply bewitched, lapping up even the casting score. Every time, the reel was changed, there would be a three or four minute blackout but no one minded; people, usually, were patiently riveted to their seats.

The films we saw were an eclectic lot —Zanjeer, Pyaasa, Dost, Five Rifles, Enter the Dragon, Yaadon ki Baraat, Casablanca, Laurel and Hardy. Guru Dutt, and Chaplin, Hrishikesh Mukerjee and Nasir Hussain, all hobnobbed with one another in that small space.

The famous family murder scene in Zanjeer with the child watching from inside the closet is still imprinted in my mind from that year; not all childhood cobwebs are easy to shake out.

Again, for some reason, Kishore’s gadi bula rahi hai, seeti baja rahi hai song from Dost makes me feel, even today, like someone just walked over my grave. I saw the same film with some amount of disinterest nearly 27 years later, and although the movie did not have me particularly excited this time, the haunting quality of Kishore’s voice unerringly sent tingles down my spine. Kishore has many far superior songs to his credit but this song strangely enough rings a special bell to me and transports me back in time to Birmitrapur.

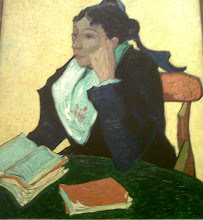

I can also not forget Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa seen the same year. To me, at the time, Waheeda Rahman was the most beautiful woman in the world. Period. Who can forget her in the Jaane Kya Tune Kahi song where she leads the poet along dark alleyways or the poignant aaj sajan mohe ang lagaa lo and the countless expressions that flit across her face—the unfulfilled longing and unrequited love? Her eyes wreak havoc and I strongly believe that women look nowhere as beautiful as they do on black and white celluloid.

To get back to that room in Birmitrapur, if per chance, there was a problem say, with the spool assembly of the projector or with the reel, and a forced interruption, the collective groan that rose up and the unease that settled in the room would be dispelled only when the film started again. Then, the bodies would slouch blissfully in their seats again till the next break.

Sometimes, my adult mind suspects, many a romance was born or snuffed out in that room, many a friendship forged or cast out. I distinctly remember a very handsome young pair, ostensibly “just friends”, mouth unabashedly the lyrics of romantic songs from the films across the room at each other or sneak out at the short breaks in seemingly inconspicuous ways. These were just staccato moments, too brief to be noticed, but I filed some such moments away in my mind, not of my own volition, and understood their relevance years later.

For us children, Sanju, Tunu, Poonam, Appu, Chitradidi, Rai, Runa, Rinamausi, and me, the best film watching days were the ones when the movies were screened at the end of a festive day. Such fun to collectively and boisterously play Holi in the club in the morning and watch a movie in the evening—good for boosting a community’s sense of camaraderie. To chant “Sar jo tera chakraye ya dil dooba jaye, aaja pyare paas hamare, kaahe ghabraye, kaahe ghabraye” in unison with our darling Johnnie Walker on screen and attempt to play tabla on our neighbour’s head in tandem, was the epitome of fun. Or celebrate Christmas with full Santa Claus regalia one night and top up with a blockbuster movie the next day; the balloons, and the streamers from the previous night still stuck to the walls as remnants of the extended good cheer. On other occasions, to watch the large lounge being cleared for the next evening’s ‘ball dance’ (waltz, what’s that?) which only the married couples were privy to. There was some amount of pique in the ‘lower ranks’ about having separate celebrations at the Officers’ Club and the Bisra Club, but it never snowballed into rabble rousing and was nixed. So, we all lived in our own worlds and wore our own rose tinted glasses.

The walk or the drive back home was naturally, a happy one with praise being heaped on the movie seen, always for its plot or the histrionics of its lead actors, never, and sadly so, for the director or film maker. That was enough for the moment; no further intellectual pontificating was expected. It was a rarity for the reputation of a film to be murdered; films were scarce and, hence, to be prized. The happy feeling stayed through the piping hot dinner that awaited us at home, thanks to our outstanding cook and housekeeper, the patriarchal Samuel (called Saamal by the family); the cloud lingered when I cuddled in my grandfather’s, Aja’s lap by the fireplace after dinner, and finally dissipated when I wedged my thin frame between Aja and Ayee later at night.

Through the snaking mists of childhood memory, I recall many different cinema watching experiences—some funny, some weird, others unbelievable—but, none romanticised by my adult mind as much as the one at Birmitrapur. I do not know whether it was the place with its unique old world charm, the quaint set of people there, or just the fact that I am here now—a 34 old year old looking back through the faint haziness of childhood nostalgia and walking down memory lane, that makes the cinema watching experience there evocative to me. Or, perhaps there is a simpler explanation. Reflecting on that phase of life reminds me of a long gone time of delight, of the cozy childhood haven of being loved by grandparents, aunts and uncles, and sundry other people loved but gone.

The Beatles give me a rationale for my eulogising of Birmitrapur so much:

There are places I’ll remember

All my life though some have changed

Some forever not for better

Some have gone and some remain

All these places have their moments

With lovers and friends I still can recall

Some are dead and some are living

In my life I have loved them all.

9 comments:

shilpa,

is it possible to live entirely on nostalgia?

to breathe ur past all the time,

or rather, is it healthy?

im just overwhelmed by my thoughts all the time.

sometimes i feel, i feel way more than most people, everything seems so intense.

haha.

love reading your blog.

hugs and kisses

Sana, no of course not sweetie. It is not possible to live entirely on nostalgia, or revel in it. There are duties and responsibilities and things to do in the present. And one lives one's life, not for oneself but for others. For all those who count on us and are part of our lives.

But, re-visiting the past, helps put things in perspective. It puts us in a more positive frame of mind I think.

Am no longer a very intense person as I once was. Practicality seeems to out weigh emotion after a point in life. But, it is also a factor of what stage of life one is in. :)

Ooh, this is the infamous article I criticised in class without knowing you wrote it!

Am no longer a very intense person as I once was. Practicality seeems to out weigh emotion after a point in life. But, it is also a factor of what stage of life one is in. :)

I still stand by what I said and therefore agree with the above. Your posts on this blog are so much more accessible and "practical" - ironically they still seem to be straight from the heart!

Bingo Rohit. Thou hast spotted the emotion that lies concealed amidst layers and layers of word wrappings in the other posts. let's say, one doesn't want to be effusive, but if things don't come straight from the heart, they mean very little. and, they fail to create an impact on the reader.

however, remember that all is a construct--both what you reveal and what you chose NOT to reveal.

have often wondered whether birmitrapur was better captured on film or in words...reading your blog convinces me that its best captured only in memories...

dont remember you growing up at the same time as watching "enter the dragon"....

anything that jogs ur memory with shailendra katyal or shailja katyal ?

Hi Shilpa,

I lived in Birmitrapur as a teenager between 69 and 75. Though I never went to Director's club, I heard a lot from my parents and sisters. Christmas party was an interesting event. When I stuck at home, my parents and sisters would return past midnight with presents..

I heard about the cook Akhtar, Anglos D'Silva, Rordrigues and so on...

When I returned home from college ( studied at Sundargarh and REC Rourkela ) I saw movies in the local theater ( cinema ) in the down town... The cinema used to have signature string of songs played on loud speakers to announce the show about to start... The same set of songs were played every day.

great. remnds me of all about bisra club, diwali party, new years party, akhtar ji, robin, tuleswar, martin. also reminds me of all the bhaiyas. holi was simple fantastic.

Hi Shilpa,

Appreciate your being able to relieve the past years of childhood. I understand you are referring here to T.C. Patnaik uncle (also referred locally as CPO saheb) and mausi. Are you Shanti apa's daughter, or elder sisters' (I understand Pratibha apa - sorry if I am missing name: memory goes for a jog after many years)? How is Vikram bhai and family? I met Manu apa few years back during a Vishwakarma Puja at their factory in Rasulgarh.

My name is Rajat (Rajat Kumar Naik), does my sister Rashmi - studying at St. Mary's ring any bell?

I very much appreciate your being able to bring back the nostalgia of the good old times at Birmitrapur(captured in the memory).

Would you be able to help me connect with Shailendra Katyal (Happy), Shailja Katyal (Shelly) or Subhadip Sen (Dodon), that are part of the chain comments to your posting? I am available on LinkedIn.

Thanks and best regards,

Rajat

Hi Shilpa,

Sorry, having Shanti apa's elder sister's name wrongly spelled. I understand it is Pratima apa. We were small kids that time, going to St. Mary's Convent School, by the time Patnaik mausa moved to TRL at Belpahar.

(The memory starts fading on names after many years - regret the error.)

Best wishes and regards,

Rajat

Post a Comment