Sunday, November 25, 2007

meaning

is a space.

i put pen on it

and think

i have confined it

to the narrow parameters

of my words.

but, meaning--

all pervading, spills over;

hugs this paper in the warmth of her arms.

time

seconds and minutes, hours and months,

years--oh heck! i have infinity

nestling against my bosom.

i am feeling vindictive today.

time thinks he can outwit me.

time thinks he can empower me.

time thinks he can rule me.

but i am lord and master.

i find a way out.

the whirring blades of my ceiling fan

whip up time into tiny chopped fragments;

too powerless to even touch me.

Film Watching at Birmitrapur Club

I traipsed jauntily down the drive way and past the oblong rose garden in red bell bottoms and a tight parrot green and brown checked shirt— a loquacious, pony tailed five year old with two missing front teeth— past the guava and custard apple orchard, the low orange and sweet lime bushes, out of the tall iron gates, along the long winding road and towards the Birmitrapur Officers’ Club. Vikram mama, whose finger I clutched, always pointed out the fireflies in the dark foliage, and then I’d walk with my head thrown backwards facing the myriad stars in the inky black December sky; a breathtaking sight seen only in such far flung places in India’s interiors. Even before we reached the top of the hill and caught a glimpse of the imposing faux colonial structure, we usually caught the strains of Cliff Richards’, “Theme for a Dream” or a Peter, Paul and Mary number or even some 1970s vintage Jagjit and Chitra Singh wafting with the breeze.

Every Thursday and Sunday, of those glorious six months of 1976 and every subsequent annual trip to Orissa that I went to my grandfather’s place in Birmitrapur, Orissa, all of us from the Patnaik clan and the other families— from the houses dotting the hills— would descend in a sizeable number for those magical film screenings at the club. Birmitrapur, in northern Orissa, has one of Asia’s biggest limestone mines, an offshoot of the Bird Company (where Amitabh Bachchan began his career as an accountant); it is a small hill station, and the club and the officer’s bungalows are nestled in the hills and their crests and troughs.

There were actually two clubs in Birmitrapur adhering to a certain hierarchy of officers and staff and workers. The Officers club was for officers of a certain standing and rank, a more elitist affair; while the other, the more popular Bisra Club, was for all staff members. Films were screened there as well, but only once a week. As for the workers in the mines and other junior staff, films were screened at a vast maidan twice a month. Many people with film watching experiences at such clubs in other parts of the country have similar tales to tell of class distinctions that existed. More often than not, the hoi polloi had to rest content with sitting behind the screen and watching the movie the reverse way, akin to the now-made-famous sequence from the recent Swades.

I am told now that in the 1950s and 1960s, films were screened only at the antediluvian but grand Director’s Bungalow, twice a month. These were English films mainly catering to the tastes of the top officers and the sizeable Anglo Indian community at Birmitrapur. The Director himself lived in Calcutta and showed up in Birmitrapur only once in a while. The film reels were always brought to Birmitrapur from Calcutta, sometimes routed through Rourkela to be screened at the local Community centre. Later, in the seventies, on popular demand, the Officers’ Club started screening home-grown Hindi movies as well. The movies were usually ones that had been released a couple of years ago, but considered recent enough by the community to generate a great deal of excitement.

Even as I shake those sepia tinted memories out of my head, I hear the clinking of ice in slender Belgium glasses, and the soft murmur of conversation, smell the smoke of Davidolf cigars and the succulent seekh kebabs from all those years back. I see Akhtar, tall and imposing, behind the counter serving drinks to all—Fanta and Coca Cola were the fashionable succour of the young and the terribly young those days before they were unceremoniously banned sometime in the ‘70s.

Soon, everyone except the uninterested would drift toward the room where films were screened on a white portable screen. The latter would sit at the bridge tables with their cognacs or coffees; occasionally, deliberating upon national politics, always munching thoughtfully over the ambrosial fare that Akhtar churned out periodically from the inner recesses of the kitchen. Some intrepid from the ‘60s generation who crinkled their aquiline noses at the ‘banal’ and ‘silly’ Hindi cinema preferred to assemble in the lounge playing chess, or table tennis or listening to the then current rage, Come September.

The room, where films were screened, was a large room with wooden chairs— not the kinds to recline on. Children sprawled, usually, on a rug in front. Sundays were for English films and Thursdays for Hindi ones. There was always a full house on Sundays when people assembled, all agog, at around 7.30 pm. Those were times before Doordarshan made film watching at home, at first, a unique novelty and then a matter of weekly routine; long before cable television reduced it to a rubble of pedestrian mendacity.

Even as the reel was loaded on the huge 1950’s Bell and Howell 16 mm film projector, that the club owned, the Mrs. Shastrys, Mrs. Rastogis, Mrs. Agrawals and Mrs. Roys would swap guava jam recipes, extrapolate on how adding a little salt to the oil on the pan prevented dosas from sticking to the pan, how Mrs. Raju had added two more rare partridges and one more Cheetal deer to her burgeoning wildlife family, how Mr. Patnaik had again bagged the first prize for gardening for his grafting of many differently coloured roses on the same shrub, and how so and so’s second son was not doing well at the REC, Rourkela. Mrs. Whiggs and Mrs. Rodericks would discuss, in low tones, the possibility of moving to London in a few years, or sending the Loilas and Lindas or Melvins away for higher education. The children munched away at sandwiches, chattering endlessly about the new Games Master at school or about Rai’s or Runa’s upcoming birthday party. It was a small world; everyone knew the goings on in everybody’s house.

When the lights were turned off and magic unwound on the silver screen, there was always a sudden hush and very palpable excitement. It was nothing short of sorcery at work and everyone was simply bewitched, lapping up even the casting score. Every time, the reel was changed, there would be a three or four minute blackout but no one minded; people, usually, were patiently riveted to their seats.

The films we saw were an eclectic lot —Zanjeer, Pyaasa, Dost, Five Rifles, Enter the Dragon, Yaadon ki Baraat, Casablanca, Laurel and Hardy. Guru Dutt, and Chaplin, Hrishikesh Mukerjee and Nasir Hussain, all hobnobbed with one another in that small space.

The famous family murder scene in Zanjeer with the child watching from inside the closet is still imprinted in my mind from that year; not all childhood cobwebs are easy to shake out.

Again, for some reason, Kishore’s gadi bula rahi hai, seeti baja rahi hai song from Dost makes me feel, even today, like someone just walked over my grave. I saw the same film with some amount of disinterest nearly 27 years later, and although the movie did not have me particularly excited this time, the haunting quality of Kishore’s voice unerringly sent tingles down my spine. Kishore has many far superior songs to his credit but this song strangely enough rings a special bell to me and transports me back in time to Birmitrapur.

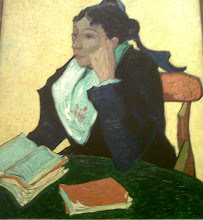

I can also not forget Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa seen the same year. To me, at the time, Waheeda Rahman was the most beautiful woman in the world. Period. Who can forget her in the Jaane Kya Tune Kahi song where she leads the poet along dark alleyways or the poignant aaj sajan mohe ang lagaa lo and the countless expressions that flit across her face—the unfulfilled longing and unrequited love? Her eyes wreak havoc and I strongly believe that women look nowhere as beautiful as they do on black and white celluloid.

To get back to that room in Birmitrapur, if per chance, there was a problem say, with the spool assembly of the projector or with the reel, and a forced interruption, the collective groan that rose up and the unease that settled in the room would be dispelled only when the film started again. Then, the bodies would slouch blissfully in their seats again till the next break.

Sometimes, my adult mind suspects, many a romance was born or snuffed out in that room, many a friendship forged or cast out. I distinctly remember a very handsome young pair, ostensibly “just friends”, mouth unabashedly the lyrics of romantic songs from the films across the room at each other or sneak out at the short breaks in seemingly inconspicuous ways. These were just staccato moments, too brief to be noticed, but I filed some such moments away in my mind, not of my own volition, and understood their relevance years later.

For us children, Sanju, Tunu, Poonam, Appu, Chitradidi, Rai, Runa, Rinamausi, and me, the best film watching days were the ones when the movies were screened at the end of a festive day. Such fun to collectively and boisterously play Holi in the club in the morning and watch a movie in the evening—good for boosting a community’s sense of camaraderie. To chant “Sar jo tera chakraye ya dil dooba jaye, aaja pyare paas hamare, kaahe ghabraye, kaahe ghabraye” in unison with our darling Johnnie Walker on screen and attempt to play tabla on our neighbour’s head in tandem, was the epitome of fun. Or celebrate Christmas with full Santa Claus regalia one night and top up with a blockbuster movie the next day; the balloons, and the streamers from the previous night still stuck to the walls as remnants of the extended good cheer. On other occasions, to watch the large lounge being cleared for the next evening’s ‘ball dance’ (waltz, what’s that?) which only the married couples were privy to. There was some amount of pique in the ‘lower ranks’ about having separate celebrations at the Officers’ Club and the Bisra Club, but it never snowballed into rabble rousing and was nixed. So, we all lived in our own worlds and wore our own rose tinted glasses.

The walk or the drive back home was naturally, a happy one with praise being heaped on the movie seen, always for its plot or the histrionics of its lead actors, never, and sadly so, for the director or film maker. That was enough for the moment; no further intellectual pontificating was expected. It was a rarity for the reputation of a film to be murdered; films were scarce and, hence, to be prized. The happy feeling stayed through the piping hot dinner that awaited us at home, thanks to our outstanding cook and housekeeper, the patriarchal Samuel (called Saamal by the family); the cloud lingered when I cuddled in my grandfather’s, Aja’s lap by the fireplace after dinner, and finally dissipated when I wedged my thin frame between Aja and Ayee later at night.

Through the snaking mists of childhood memory, I recall many different cinema watching experiences—some funny, some weird, others unbelievable—but, none romanticised by my adult mind as much as the one at Birmitrapur. I do not know whether it was the place with its unique old world charm, the quaint set of people there, or just the fact that I am here now—a 34 old year old looking back through the faint haziness of childhood nostalgia and walking down memory lane, that makes the cinema watching experience there evocative to me. Or, perhaps there is a simpler explanation. Reflecting on that phase of life reminds me of a long gone time of delight, of the cozy childhood haven of being loved by grandparents, aunts and uncles, and sundry other people loved but gone.

The Beatles give me a rationale for my eulogising of Birmitrapur so much:

There are places I’ll remember

All my life though some have changed

Some forever not for better

Some have gone and some remain

All these places have their moments

With lovers and friends I still can recall

Some are dead and some are living

In my life I have loved them all.

Nature’s Bounty is Here!

Every year when we make our customary summer trip to Orissa, I am amazed afresh with the wealth of nature’s bounty there. It is not an ostentatious or showy beauty that dazzles and craves for attention. Rather, it is just there, almost self-effacing, a mute and ennobling presence, that humbles even as it evokes pride.

Sometimes I feel that since eastern India is so rich in natural beauty, the people here are dressed plainly in subdued colours to offset it; in western India, Gujarat or Rajasthan, for instance, people need to be dressed in brightly coloured clothes because the landscape and hence, visual imagery is so dry and barren. Of course, it is a very subjective hypothesis.

To get back to the story without digressing… If you manage to stroll by the Kathjodi river, you find that water fowl frolic there in the afternoon and cranes glide lazily albeit majestically over the water. No whiteness on earth can match the pristine whiteness of their wings and slender necks. If you focus solely on the flapping of their wings and are also conscious about the chopping movement of the river underneath, you will feel almost transported over the waves by an optical illusion.

My Pisi’s house in Cuttack, where I have spent many a childhood afternoon, has a lush green compound. Here are two Kadamba trees, a jamun tree, two mango trees, an impressive neem , a verdant guava tree, a bela tree, and many coconut trees and banana trees. A certain kingfisher comes daily in the afternoon and sits on a particular thin branch of a neem tree here, at almost the same time. It happily sways along with the branches as the breeze passes through them. A couple of times, I have even spotted a Hoopoe bird strutting on the ground. Once I was lucky enough to see a rare Sunbird flitting in the foliage near the tank in the compound, its wings whirring like the blades of toy helicopters. I have heard a Coppersmith too but not spotted it. There are these robust magpie-robins that dart in and out of the branches of the neem as if playing hide and seek, and tiny, delicate blue-black Jays that serenade each other. Sometimes, I see some birds, whose names I do not know, that look like Swallows minus tails and fattened on a diet of cheese. They remind me of the portly nuns in the convent from “The Sound of Music” and it seems that they will just burst into full throated song. Once, a flash of mustard and flaming orange winged past briskly. And even as I stared in open mouthed wonder at this gorgeous beauty, it was gone…as quickly as it had come. Are there Birds-of Paradise in India?

When the river bed is quite dry with only patches of water dotting the parched earth, you see buffaloes wading in the water, heads sticking out, bodies glistening like those of well oiled wrestlers in the ring. Cattle egrets sometimes sit on them and do what nature ordained them to—peck at tiny insects on the backs of the buffaloes. (The river also has its moods. It sparkles silver in the morning sunlight, glows golden in the afternoon, mellows down somnolently to a grey blue in the evenings. Steel grey shadows flit through the water when clouds or a flock of birds are passing overhead ).

At Aja’s home in Bhubaneshwar, matronly pigeons (of all shapes and sizes), slender doves, homely and ebullient little sparrows, sprightly mynahs, shrewd parrots, elf-like squirrels and raucous crows often peep in from the window to say ‘hello’. Spiders continue weaving their gossamer threads (dreams?) oblivious to all else. Grasshoppers and merry crickets do a langorous, summer afternoon waltz near the flower beds. Butterflies, with gossamer wings as thin as dried peepul tree leaves are other regulars. Invisible koels pour their mellifluous notes into the otherwise quiet afternoon air. With the rains, peacocks will also come to express their joy of living and to add to yours. But even now, their lonesome cries rent the air in the evenings.

At my in laws’ house, on the branches of a distant Krushnachuda tree, I spot another bird, whose name I don’t know, peeping out saucily from behind a flaming vermillion flower, and I rue the fact that I do not know who she is. A golden brown mongoose with her babies trooping behind her in fine array frequents the low shrubs. Not to forget the occasional dog that strays onto the lawns, has a siesta or a fiesta as the case may be; sometimes, a troop of monkeys, babies et al that seem to be replicating our lives in all their domestic detail.

Nature’s bounty is here! Spring is in the air!!

Monday, November 19, 2007

telephone

you pick it up.

i try to talk,

but don't succeed.

i just give up.

silence punctuates

our conversation.

questions asked.

answers given.

assurances felt.

tempers driven.

verbal battles.

love is given.

love is taken--

all in silent meditation.

night

and fractures into two

the indivisible one of daytimes.

vignettes on rain

the rain

taps my window pane

in quiet secrecy

and i, away from

all matter, all pain

reach where i cannot be.

i find you with me.

once again the rain

in the bustle of the city.

outside the crowded bus

waiting to strike softly

as you emerge carelessly.

black shoe sharp nail

crushes a rose petal; the rain

has carefully struck again.

seven in the evening.

i catch you unawares

in the dark; drenched

under the neem

on that stonehearted bench.

why is your lonesome pain

making a date with rain?

if you come this way

through winding, narrow lanes

where light peeps from behind curtains drawn

blushing coyly at the night,

find your way though the doors are closed, and the roads depeopled still.

search out the solitary footprints

that in waiting

paced up and down the difficult pathways.

see how they lead up rickety stairs

winding upwards towards some faint light.

quick. cross the threshold

in brisk steps.

lest your footsteps too

stop outside like mine.

Thursday, November 15, 2007

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

On being an Oriya

That night, I found myself sitting on the swing in the balcony, a strong hot coffee in hand replaying the classroom scene. The student’s question had flummoxed me, and had me trip over my own words because I had never felt a need to rationalize the issue consciously. Who ever sits and cogitates on “Who am I?” The whole enterprise, in today’s express paced times-- where we, mouse potatoes, measure out our lives with coffee mugs over bits and bytes sounds absurd. Only philosophers engage in such reflections. And, where on earth is the time? So, there I was: As Atlas carrying a tremendous burden and unable to shrug it off. The tedious question of insidious intent kept clawing at my head. So, I did what we usually do when faced with stubbornly sticky questions—toss them away.

One of the binary opposites jostling amongst many in my head was whether I am a non-resident Oriya or an honorary Gujarati. How does it matter was the immediate afterthought and I chucked the thought away again. Anyway, here I am now, pounding away on the keyboard like a maniac and chewing on the cud.

So, what has it been to be an Oriya? Feeling elated every year on my annual trips to Orissa—to Karanjia, Bhubaneshwar, Cuttack, and earlier Koraput, Rourkela and Birmitrapur, when gazing upon all that natural beauty—the lush greenery, the ripe fields, the lotuses and lilies in the myriad pools all over the place, the many banana, papaya, jackfruit and coconut trees even in the humblest of homes? What was it about the old-world antiquated charm and feel of the place as though you were in another world? Stone temples with their beauty and simplicity somehow stirred the hidden atheist in you and made you feel spiritual, if not religious.

Even as the Howrah Express snaked its way into the state in all those train journeys of my childhood, we would be looking out through the windows glued to the verdant beauty of the paddy fields, the streams and rivulets, the dense forests, and the humble homes and villages we passed. Papa would sometimes start singing some Oriya songs he had heard in his childhood (clearly etched in my memory even today)—Tulasichaura mule, Rangani gachha tale, sanja batti libhi libhi jaye, jaye lo/ sanja batti libhi libhi jaye… and look happily entranced at “going home.”

What has it been to be an Oriya? Feeling excited every time a textbook in school mentioned Orissa—whether it was the geography textbook talking about iron ore mines in Orissa, or a mention of Jagannath Puri and Rathyatra somewhere else, or even upset when a story in the class 6 Gujarati textbook referred to Orissa as a very poor state (garibdi) and the inhabitants as raankdi. Feeling exasperated when people often asked, Orissa-- e wali kyaan che?” (Orissa—where on earth is it? ) A neighbour once asked, “Kya who Pakistan ke paas hai?” Another college going girl asked me whether Gujarati was taught in schools in Orissa, and when I roared a “NO”, asked why not. Gritting my teeth at her complete lack of awareness about another state in her own country, trying to patiently point out that Orissa is a state in eastern India, I retorted, “Do they teach Oriya in schools here?” She looked at me as though I were daft, threw me a sympathetic look and sidled away.

Since childhood, Papa inculcated in us sisters, a love for the handicrafts of Orissa. He was so much taken by their simplicity of form, aesthetic sense, use of natural raw materials abundantly available in Orissa, beautiful colour palettes, typical and traditional motifs, and range, that it was only natural, that in course of time, we grew to love them too. Whether it is the lacquer work-cane boxes of Navarangpur, dhokra (lost wax process) artifacts, figurines chiseled from buffalo-horn, tribal terracotta ware, pattachitra paintings, tribal bell metal jewelry, Pipli appliqué work wall hangings, wooden toys, —all found a pride of place both at my parents’ home and later, when I got married, in mine. There is something about this rich repository of our crafts that tugs at the heart strings, and moves, especially when watching craftspersons making them. It is a love that found fruition in NID, Inshallah, when I got involved with craft documentation as a course. Does all this qualify to make me an Oriya?

How can one forget the handlooms of Orissa, especially ikat or tie and dye fabrics, known as bandhas? Handlooms reflect the essence of the traditional way of life; the loom is an intrinsic part of the state’s folklore. These handwoven textiles have such an amazing depth and range, vim and vigour that have evolved over generations. I grew up observing the ladies of the Oriya families settled in Ahmedabad drape these saris on get togethers or other functions of the association. Mummy's own collection of exquisite bomkais, sambalpuris and saktapar saris were always the envy of the neighbourhood and a matter of pride for us girls. There’s nothing like wearing kurtas made of Sambalpuri cloth in summers—very conducive for the skin and they are my staple office-wear in summer.

Pithas are another unforgettable relic in childhood memories. Some of my friends were amazed with the chunchipatra pitha, haldipatra pitha, and podopitha mummy made. But, my personal favourite is the arisapitha, particularly the sugar variety because both Ayee and Mama were experts at making them and it was like a bonanza for a gluttonous child staring greedily at them while they were being made and the aroma filled up the whole house.

Is one an Oriya if one speaks Oriya (albeit with an accent)? I remember when those of us who have grown up in Ahmedabad met during get-togethers, Nilamani Mohanty uncle always used to come up to us children and urge, “Speak in Oriya amongst yourselves, not in English or Hindi.” To our immature minds, it was a quaint thing to do (our schooling made it only natural for us to converse in English); at the time, some of us used to think it was wearing our Oriya-ness on our sleeves and being parochial. The wisdom of what he was saying occurred-- to me at least— years later, and now a parent myself, am happy that my daughter speaks Oriya too.

In any case, after class XII, the urge to learn to read and write Oriya took hold of me, and procuring a Barnabodha tutored myself to learn. Of course, writing Oriya was restricted to writing letters to grandparents, and later to grandparents-in-law. Sushmita, Nilamani Mohanty uncle’s daughter was an inspiring influence who in our growing up years could read Janamamu with ease and élan. Growing up listening to Tapoi, tales of Jagannath, and many other folk tales--- some from either or both my parents, some from ayee and others from mama, my Jejema, or even happily discovering a ‘Folk Tales of Orissa” in a Delhi bookstore while strolling on Janpath one winter afternoon as a student at JNU--- was a treat, and these were often an entry point into Oriya culture. We have grown up on these tales no less than any child born and brought up in Orissa. As adults, at least two of us, Sunita and I have shared common interests in and books on Orissa’s history, folklore, iconography, temple architecture, crafts, rites and rituals. We continue to do so.

Once, soon after we were married, a cousin visited Anshuman and me in Delhi where we were then living. During a long conversation over lunch, which essentially comprised posto bada, phoolkobi patua, khoda sago, bilati baigana khata, dahi salad, rice and mooga dali, the cousin leaned across the table and remarked, “What do you non-Oriyas know about Oriya culture, eh?” The remark stung to the quick, not just because of its rudeness and audacity, but also because it seemed unfair. Why should one have to defend one’s Oriya-ness, lack of it or part of it, to those brought up in Orissa? Why should it be held as something against one? Of course, I spent the greater part of the next forty minutes or so delivering an impassioned speech on how wrong he was; asked him five questions on Oriya history, geography, etc. with a great deal of theatricality and silenced him. In hindsight, I feel it was not necessary to do that. The episode amuses me, and makes me reflect in a different way today. If this be so, then what am I doing, venting my angst, justifying the integral Oriya half/part of myself here? This whole exercise of penning these thoughts down becomes paradoxical and deconstructive.

There is a beautiful story in the Upanishads which explains the oneness of things. Shvetaketu asks Sage Uddalak, his father, to tell him what is the essence of things, of being. Uddalak asks his son to break open the seed of the fig tree. Doing so, Shvetketu finds nothing inside and the father points out how that nothingness leads to the birth and growth of a new tree from the seed. Uddalak calls that nothingness, the essence of being.

We, who live outside the state of our origin, straddle two worlds, imbibe two cultures, are rooted in both and are hence, more cosmopolitan, more heterodox, more accepting of plurality and diversity. People may scoff and remark we are “rootless”, but we probably have the best of both. I grew up here with a heady cocktail—an Oriya in origin, a Gujarati at heart. While I carry in my head the poetry of Orissa’s rivers and streams, her folklore and art, my heart is full of the love and acceptance that is so quintessential of Gujarat.

Inclusive Design: Enabling Spaces

Predictably then, like other public utility buildings such as educational institutes, parks, hotels, cinema halls, housing complexes, banks, government offices and the railway and bus stations, these architectural edifices are woefully insensitive to the needs of those whose ability to move around is restricted-- the elderly, and persons with physical impairments.

People with locomotor impairments are significantly disadvantaged by the design of the typical retail stores and malls, and find that moving around in them can be a nightmare. To start with the floors, including highly polished, marble and terrazzo floors and those that have been treated with floor finishes are inherently, dangerously slippery. It takes tremendous effort to walk carefully on them. Wet weather conditions and poor housekeeping leading to wet floors worsen the situation. There are no seats, sofas, or chairs where they can sit or rest in the midst of their shopping which leads to discomfort, physical pain and exhaustion. For wheelchair users, malls are effectively off-limits because they are not always barrier free even if they do have lifts, ramps, and special toilets. Often, the ramps are excessively steep and special configuration steps, railings, lifts equipped with handle bars are conspicuously missing.

While the physical impairment itself may cause the difficulty in mobility, ableist environments which are not accommodating enough lead to dis-abling situations. The burden of disability must necessarily shift from the individual to society; we need to re-examine the built environment and technology. This is because when disability combines with restricting factors in the environment such as social attitudes, a lack of information and access to quality services it results in a situation of handicap. Handicaps perpetuate the exclusion of people with disabilities from mainstream society by violating their human right to a life of dignity and equal opportunity.

Surely, the mobility of people through such public spaces can be made less stressful in a way that includes the needs of all ages and abilities. This is where Inclusive Design comes in: it is a way of designing policies, services, products and environments in a sustainable manner so that they are usable and appeal to everyone regardless of age, and ability by working with users to remove barriers in the social, technical, political and economic processes underpinning building and design. Doing so, will help build a more integrated and inclusive society that can truly carry us into a new India.

Tuesday, November 13, 2007

november rain

hey, what ever happened to those assiduous "dear diary" decades when single lined pages stood in for a confidante and patient listener? when every entry began predictably with, "today, I ...." meandered aimlessly through " school, home, friends, mummy and papa..." and convulsed unerringly into, " feel lonely...miserable" (ho humm). when you wrote warily because you didn't want to hurt anyone's feelings with what you'd written? when you wrote in such a way that only you could truly understand what you'd written? when you wrote because you didn't want to shed tears on your cheeks, but allowed them to flood into the inner most recesses of your soul?

today, i do not want to read those diaries, i do not want anyone to read those diaries, and yet do not have the heart to throw those musty-smelling private mementoes away. they are me, in a certain age and time. they are. whatever they are worth. such vanity. and miserly possessiveness. so they remain firmly enconsed in the bedroom loft where they have been for years, along with other bric-a-brac and senseless relics from the past. We are all collectors of some sort or the other. hoarders. some of us hoard objects. some wealth. and some memories.